The so-called “encapsulated interest” account of trust, developed by Russell Hardin together with other interested scholars, draws together an important body of thought about trust and its meaning in social and personal relations.1 Trust, under this account, involves considered expectations about the interests of others to behave in a trustworthy manner. Some scholars argue that trust of this sort is not trust at all. Laurence Becker (Becker 1996), for example, argues that “cognitive” trust, of the sort discussed in the encapsulated interest account, is indistinguishable in the final analysis from knowledge and power. Becker over-simplifies considerably; it is clear both that many instances of power over another, or knowledge of another’s interests, do not create trust, and that even when power may engender trust, the concepts remain distinguishable. For example, as Hardin argues (Hardin forthcoming), trust does not apply in a relationship where I am holding a gun to your head; while I certainly have power over you, and know that you have an overwhelming interest to do what I tell you to do, the degree of certainty that I have about your interests renders trust irrelevant. While power, and knowledge of the effects of power on interests, may clearly affect trust under certain circumstances, the concepts should not be conflated.

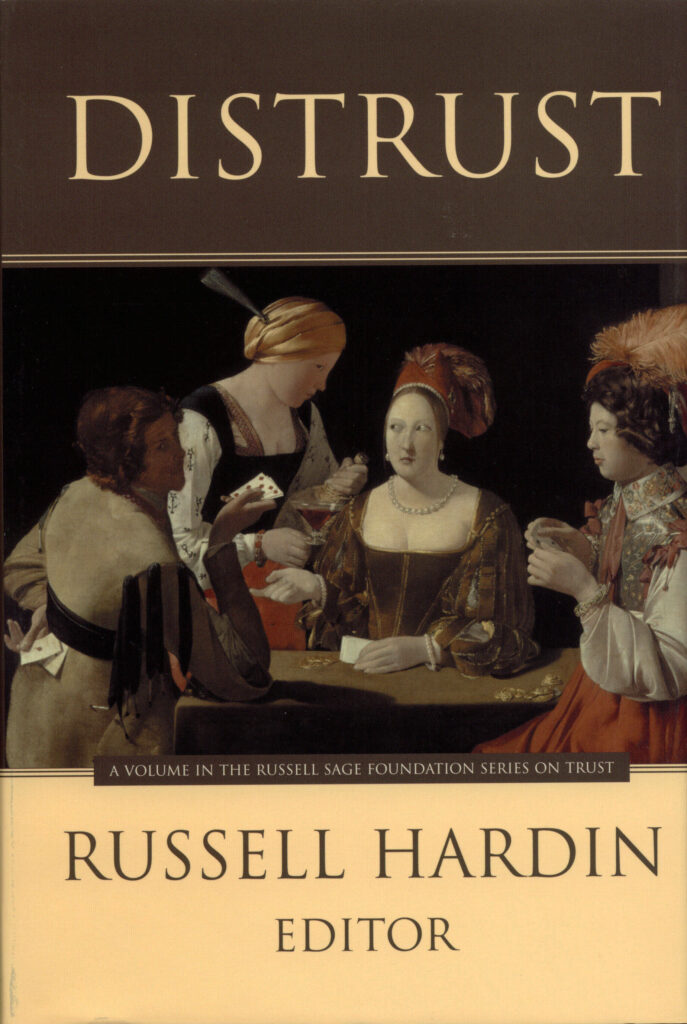

Henry Farrell, “Trust, Distrust, and Power” in Distrust, ed. Russell Hardin (Russell Sage Foundation, 2004).